Turka

Sambir district, Lviv region

Sources:

- Virtual Shtetl. Turka

- Jewish encyclopedia of Brockhaus & Efron

- Wikipedia. טורקה

Photo:

- Jewish Cemeteries Initiative. Turka Jewish Cemetery

- Center for Jewish art. Turka

- Biblioteka Narodowa Polona. Turka

- Wikipedia. Турка

- Virtual Shtetl. Turka

- Jewish encyclopedia of Brockhaus & Efron

- Wikipedia. טורקה

Photo:

- Jewish Cemeteries Initiative. Turka Jewish Cemetery

- Center for Jewish art. Turka

- Biblioteka Narodowa Polona. Turka

- Wikipedia. Турка

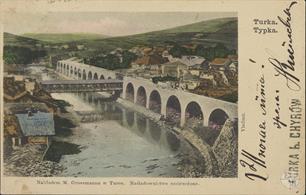

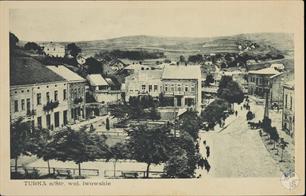

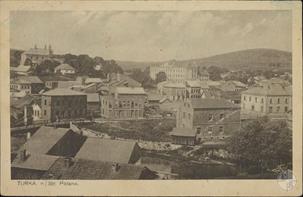

Turka (Ukrainian: Турка, Yiddish: טורקא) is a city located at the confluence of the Stryi River and the Yablunka River in Sambir Raion, Lviv Oblast.

The first references to the Jews in Turka date back to the 16th century, when the locality was still a village. In 1730, the town was granted municipal rights and Jewish people began to arrive there. At the beginning of the 20th century, along with the construction of the railway, Turka entered a period of dynamic development. It became a local administrative and economic centre for about 80 villages. It became a hub of the wood industry (four sawmills, including a huge sawmill with twelve gates and a large, steam-driven factory with over 500 Ukrainian, Polish and Jewish workers), with large-scale export of building materials and boards.

In 1880, there were 2,368 or 2,398 Jews living in the town, and in 1910 their population more than doubled, amounting to 4,887 people, which constituted about 50% of the total population (in 1880 – 4,634 people). Moreover, the mayor of the town was also a Jew.

The majority of the Jewish population in Turka and its surroundings came from the working class, middle class, and many were engaged in various crafts.

During the interwar years, Turka continued to develop – many new sawmills were established, providing employment to many Jews. Most of the Jewish children were enrolled in Polish schools and only a small group received traditional education.

The first references to the Jews in Turka date back to the 16th century, when the locality was still a village. In 1730, the town was granted municipal rights and Jewish people began to arrive there. At the beginning of the 20th century, along with the construction of the railway, Turka entered a period of dynamic development. It became a local administrative and economic centre for about 80 villages. It became a hub of the wood industry (four sawmills, including a huge sawmill with twelve gates and a large, steam-driven factory with over 500 Ukrainian, Polish and Jewish workers), with large-scale export of building materials and boards.

In 1880, there were 2,368 or 2,398 Jews living in the town, and in 1910 their population more than doubled, amounting to 4,887 people, which constituted about 50% of the total population (in 1880 – 4,634 people). Moreover, the mayor of the town was also a Jew.

The majority of the Jewish population in Turka and its surroundings came from the working class, middle class, and many were engaged in various crafts.

During the interwar years, Turka continued to develop – many new sawmills were established, providing employment to many Jews. Most of the Jewish children were enrolled in Polish schools and only a small group received traditional education.

Turka was located far from large Jewish centres, but the Zionists were quite active there. From the beginning of the 1920s, there were many Zionist youth groups in the town, and the pioneering Aliyah (Jewish immigration to Palestine) continued throughout the interwar period – either legally or illegally.

Hashomer Hatzair was the first among Zionist organisations to appear in the town. It was headed by Abba Hushi. For several years, it was the only youth movement in Turka.

Later on, Bnei Akiva gained much popularity, attracting the majority of tertiary and high school students. Akiva formed Hebrew language learning clubs, sent its outstanding members to hachsharot (centres for future settlers, preparing for pioneering life), and worked for the Jewish National Fund.

There were also other Zionist organisations in the town, such as HeHalutz (led by Mendel Filinger) and Jugent (led by Chaim Pelech and others). The Zionists introduced the custom of the Sabbath encounters to Turka.

Young Jews would gather in the headquarters of their organisations for assemblies, or venture outside the town, where they would hold discussions on current affairs. The meeting place was called Szomra’s Grove.

Among the political parties, the General Zionists and the Mizrachi were the most active. There was a branch of Poale Zion in the town, headed by Szlomo Pelech. The Bund and Betar were not very popular.

Hashomer Hatzair was the first among Zionist organisations to appear in the town. It was headed by Abba Hushi. For several years, it was the only youth movement in Turka.

Later on, Bnei Akiva gained much popularity, attracting the majority of tertiary and high school students. Akiva formed Hebrew language learning clubs, sent its outstanding members to hachsharot (centres for future settlers, preparing for pioneering life), and worked for the Jewish National Fund.

There were also other Zionist organisations in the town, such as HeHalutz (led by Mendel Filinger) and Jugent (led by Chaim Pelech and others). The Zionists introduced the custom of the Sabbath encounters to Turka.

Young Jews would gather in the headquarters of their organisations for assemblies, or venture outside the town, where they would hold discussions on current affairs. The meeting place was called Szomra’s Grove.

Among the political parties, the General Zionists and the Mizrachi were the most active. There was a branch of Poale Zion in the town, headed by Szlomo Pelech. The Bund and Betar were not very popular.

|

|

|

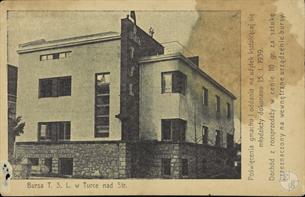

| The most beautiful old building, Art Nouveau style. Mitskevycha street | Old Catholic Church in Turka, 2011 |

Turka also boasted Jewish organisations focusing on knowledge, literature and art. In 1920s, the Perec Club started its activities. The founders were Zerach Szajn (chairman until the delegation), Szlomo (Ini) From (secretary), Lewi Hamerman (vice-chairman), Eljachu Montel (chairman of the culture committee), Doctor Norbet April (honorary chairman), Pesi Szpigler, and Lejbusz Mandel. Apart from educational activities, the Perec Club also organised on-going socio-political educational campaigns. The results were astounding – famous Jewish theatres, theatrical troupes, actors and directors who visited Turka performed in front of crowded auditoriums (e.g. the Prisament and Hart theatre troupe staged eight to ten performances in Turka in just two weeks).

In the first half of the 1930s, the Perec Club organised three open ‘literary courts’ on the works: I am Hungry by George Fink, All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque, Jean-Christophe by Romain Rolland. The events took place in a tightly filled room; the last one was held in the hall of the Sokуł (Falcon) gymnastics organisation.

In the 1930s, the Jewish Sports Club was formed, with a very good football team. The stars of the team were Josza Bernanke, Ben-Cjon Eisman, Kalman Meiner and Mani Laufer.

In the second half of the 1930s, the situation of Jews in Turka began to change. The town, like many others throughout Poland, was affected by anti-Semitism, and especially by the calls for the boycott of Jewish venues. Non-Jewish shops, hairdressing salons and bakeries in the town began to add the word ‘Christian’ to their signboards.

Anti-Semitic sentiments were especially noticeable among the Ukrainian population that lived on the outskirts of the town. Ukrainians repeatedly attacked Jewish passers-by, who often defended themselves and responded by fighting back. This was the case, for example, during one of the Sabbath eves, when the Jews were leaving for their homes.

There was a brawl in which the Ukrainians were severely beaten up by the Jews. The atmosphere in the town became very tense. The Zionist youth prepared self-defence, and rumours about a planned attack on Jewish shops on the day of the fair, that is on Wednesday, were circulating around the streets. The Jews, however, turned to the local authorities for help, which helped prevent the escalation of violence.

In 1921, about 4,200 Jews lived there, which was about 40% of total population.

In the first half of the 1930s, the Perec Club organised three open ‘literary courts’ on the works: I am Hungry by George Fink, All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque, Jean-Christophe by Romain Rolland. The events took place in a tightly filled room; the last one was held in the hall of the Sokуł (Falcon) gymnastics organisation.

In the 1930s, the Jewish Sports Club was formed, with a very good football team. The stars of the team were Josza Bernanke, Ben-Cjon Eisman, Kalman Meiner and Mani Laufer.

In the second half of the 1930s, the situation of Jews in Turka began to change. The town, like many others throughout Poland, was affected by anti-Semitism, and especially by the calls for the boycott of Jewish venues. Non-Jewish shops, hairdressing salons and bakeries in the town began to add the word ‘Christian’ to their signboards.

Anti-Semitic sentiments were especially noticeable among the Ukrainian population that lived on the outskirts of the town. Ukrainians repeatedly attacked Jewish passers-by, who often defended themselves and responded by fighting back. This was the case, for example, during one of the Sabbath eves, when the Jews were leaving for their homes.

There was a brawl in which the Ukrainians were severely beaten up by the Jews. The atmosphere in the town became very tense. The Zionist youth prepared self-defence, and rumours about a planned attack on Jewish shops on the day of the fair, that is on Wednesday, were circulating around the streets. The Jews, however, turned to the local authorities for help, which helped prevent the escalation of violence.

In 1921, about 4,200 Jews lived there, which was about 40% of total population.

Synagogue complex. It was built in the middle of the 19th century, consisted of 4 buildings, the main of which was a unique synagogue with two baroque towers. A school and several "professional" synagogues were located nearby.

After the war, the city power station was placed in the main building, in two others - the furniture manufacturing artel. As of 2012, both towers were dismantled, the carpentry workshop acted in the synagogue building. Address - st. Jerelna, 2

After the war, the city power station was placed in the main building, in two others - the furniture manufacturing artel. As of 2012, both towers were dismantled, the carpentry workshop acted in the synagogue building. Address - st. Jerelna, 2

Before the Second World War, about 6,000 Jews lived in Turka, making up about 41% of the town's population. About 7,000 Jews lived in the surrounding settlements.

In 1939 the Soviet army entered the town, and in July 1941 the German occupation of Turka began. Ukrainians perpetrated many anti-Jewish attacks. Jews were forced to work as slave labourers. In the winter of 1941 and 1942, a great famine swept through the town.

On 7 January 1942, about 500 Jews were murdered at the mass graves in the vicinity of the local brickworks. A few months later, in June 1942, Germans killed about 150 people, most of them children.

On 4 August 1942, the so-called extermination Aktion began, lasting four days. It was preceded by false information announced on 1 August, concerning the creation of a ghetto in the town. Jews from neighbouring villages and small towns were resettled to Turka. During the Aktion, some 2,000-4,000 people were taken to the extermination camp in Bełżec. Many of them tried to escape to Hungary or take refuge in the surrounding forests, but most were murdered or denounced by the local population.

On 1 December 1942, the last group of Jews was deported to the Sambor ghetto, which had over 3,000 prisoners. Many people died there from hunger and diseases, and from time to time small groups of young Jews were transported to the camp at Janowska Street in Lviv.

In 1943, three liquidation Aktions were carried out in the Sambor ghetto: on 13 February, when about 500 Jews were killed, on 14-18 April, when about 900 people were killed, and on 20 May, when 550 people were transported to the concentration camp at Majdanek and 70-80 to the camp at Janowska Street in Lviv.

The final liquidation of the Sambor ghetto took place. It lasted several days and resulted in the murder of more than 1,000 prisoners.

Only ca. 30 Jews from Turka survived World War II.

In 1939 the Soviet army entered the town, and in July 1941 the German occupation of Turka began. Ukrainians perpetrated many anti-Jewish attacks. Jews were forced to work as slave labourers. In the winter of 1941 and 1942, a great famine swept through the town.

On 7 January 1942, about 500 Jews were murdered at the mass graves in the vicinity of the local brickworks. A few months later, in June 1942, Germans killed about 150 people, most of them children.

On 4 August 1942, the so-called extermination Aktion began, lasting four days. It was preceded by false information announced on 1 August, concerning the creation of a ghetto in the town. Jews from neighbouring villages and small towns were resettled to Turka. During the Aktion, some 2,000-4,000 people were taken to the extermination camp in Bełżec. Many of them tried to escape to Hungary or take refuge in the surrounding forests, but most were murdered or denounced by the local population.

On 1 December 1942, the last group of Jews was deported to the Sambor ghetto, which had over 3,000 prisoners. Many people died there from hunger and diseases, and from time to time small groups of young Jews were transported to the camp at Janowska Street in Lviv.

In 1943, three liquidation Aktions were carried out in the Sambor ghetto: on 13 February, when about 500 Jews were killed, on 14-18 April, when about 900 people were killed, and on 20 May, when 550 people were transported to the concentration camp at Majdanek and 70-80 to the camp at Janowska Street in Lviv.

The final liquidation of the Sambor ghetto took place. It lasted several days and resulted in the murder of more than 1,000 prisoners.

Only ca. 30 Jews from Turka survived World War II.

Jews of Turka were mainly engaged in trade and crafts when almost all the craftsmen were Jews and they also worked for the gentiles. The main crafts they were engaged in were: tailoring, shoemaking, sewing, literature, carpentry. There were Jews who were engaged in the wood industry when the large sawmills were mainly Jewish owned. Also all the free professionals, with the exception of two senior doctors, one of whom was the director of the hospital and the other appointed by the Ministry of Health, were Jews. About 95% of the bankers were Jews. The Jews of the surrounding settlements made a living from agriculture, from grocery stores and taverns. There were very few Jewish government officials, but there were two Jews at the head of the local council: one named Shechter and the other Dr. M. Landes (1912).

The main streets of the town were full of Jews and there were no Christians. Only in the years 1910 - 1909 ( 1599 - 1907 ) did the gentiles begin to return to the main streets. Two gentile restaurants were opened in Bhila, and then grocery stores and a Ukrainian grocery store. More Christian businesses and trading houses did not open for about twenty years until, in the mid-1930s, Christians opened shops in various fields of business in the center which until then was dominated by Jews.

The main streets of the town were full of Jews and there were no Christians. Only in the years 1910 - 1909 ( 1599 - 1907 ) did the gentiles begin to return to the main streets. Two gentile restaurants were opened in Bhila, and then grocery stores and a Ukrainian grocery store. More Christian businesses and trading houses did not open for about twenty years until, in the mid-1930s, Christians opened shops in various fields of business in the center which until then was dominated by Jews.

- Home

- Shtetls

- Vinnytsia region

- Volyn region

- Dnipro region

- Donetsk region

- Zhytomyr region

- Zakarpattia region

- Zaporizhzhia region

- Ivano-Frankivsk region

- Kyiv region

- Kropyvnytskyi region

- Luhansk region

- Lviv region

- Mykolayiv region

- Odessa region

- Poltava region

- Rivne region

- Sumy region

- Ternopil region

- Kharkiv region

- Kherson region

- Khmelnytskyi region

- Chernihiv region

- Chernivtsi region

- Cherkasy region

- Crimea

- Synagogues

- Cemeteries

- Objects & guides

- Old photos

- History

- Contact

Jewish towns of Ukraine

Jewish towns of Ukraine

My shtetl

My shtetl

Donate