Kremenets

Ternopil region

Sources:

- Jewish encyclopedia of Brockhaus & Efron

- Russian Jewish encyclopedia

- Pinkas Hakehillot Polin: Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities, Poland, Volume II, published by Yad Vashem, Jerusalem

- FB Group Типовий Кременець

- El Folio Все фотографы и фотоателье Волынской губернии

Photo:

- Eugene Shnsider

- FB Group Krzemieniec i okolice do 1939 roku

- Dmitry Vilensky, Mikhail Kheifets. The Center for Jewish Art

- Photo archive by Alter Katsizne

- Photo archive by An-sky's expedition

- Українські Архітектурні Пам'ятки. Спадщина. Кременець

- Jewish encyclopedia of Brockhaus & Efron

- Russian Jewish encyclopedia

- Pinkas Hakehillot Polin: Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities, Poland, Volume II, published by Yad Vashem, Jerusalem

- FB Group Типовий Кременець

- El Folio Все фотографы и фотоателье Волынской губернии

Photo:

- Eugene Shnsider

- FB Group Krzemieniec i okolice do 1939 roku

- Dmitry Vilensky, Mikhail Kheifets. The Center for Jewish Art

- Photo archive by Alter Katsizne

- Photo archive by An-sky's expedition

- Українські Архітектурні Пам'ятки. Спадщина. Кременець

According to some sources, the Kremenets fortress was built back in pre-Christian times in the 8th-9th centuries, and there is a hypothesis that after the formation of the Kyiv state in the 9th century, Kremenets became part of it. In addition, the first mentions of Kremenets are found in Polish encyclopedic dictionaries under 1064.

The first mention is the Ipatiev Chronicle, which speaks of Kremenets as a city of the Galicia-Volyn principality, which in 1227 the Hungarian king Andrew II failed to take after the capture of Terebovlya and Tikhoml.

In the winter of 1240-1241, Batu Khan approached the city with a large Mongol horde, but, unlike other fortresses, he could not capture the Kremenets castle. Later, in 1254, near Kremenets, the troops of Daniil Galickiy defeated the Tatar formations of Khan Kuremsa. After 5 years, in 1259, Daniil's brother, the Russian prince Vasilko, had to destroy the fortress in Kremenets under the terms of an agreement with the temnik Burundai. The fortifications were restored only during the reign of Mstislav Danilovich at the end of the 13th century.

The first mention is the Ipatiev Chronicle, which speaks of Kremenets as a city of the Galicia-Volyn principality, which in 1227 the Hungarian king Andrew II failed to take after the capture of Terebovlya and Tikhoml.

In the winter of 1240-1241, Batu Khan approached the city with a large Mongol horde, but, unlike other fortresses, he could not capture the Kremenets castle. Later, in 1254, near Kremenets, the troops of Daniil Galickiy defeated the Tatar formations of Khan Kuremsa. After 5 years, in 1259, Daniil's brother, the Russian prince Vasilko, had to destroy the fortress in Kremenets under the terms of an agreement with the temnik Burundai. The fortifications were restored only during the reign of Mstislav Danilovich at the end of the 13th century.

In the XIV century the city was part of Lithuania and Poland. The Magdeburg Law was received in 1431.

On April 4, 1536, the King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania Sigismund I the Old handed over Kremenets with the surrounding villages to his wife Bona Sforza, who owned the castle in 1536-1556 and after whom, according to one version, the castle hill was named. Bona significantly strengthened the castle, which at that time had three towers and rather high walls with cannons. Inside the castle there were barracks for the garrison, various household objects, powder flasks.

In the autumn of 1648, the Cossack colonel Maxim Krivonos completely destroyed the castle after a six-week siege. Since then, the fortress has not been restored.

In 1793-1917, Kremenets was part of the Russian Empire. Since 1921, the city belonged to Poland, since 1939 - as part of the Ukrainian SSR.

On April 4, 1536, the King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania Sigismund I the Old handed over Kremenets with the surrounding villages to his wife Bona Sforza, who owned the castle in 1536-1556 and after whom, according to one version, the castle hill was named. Bona significantly strengthened the castle, which at that time had three towers and rather high walls with cannons. Inside the castle there were barracks for the garrison, various household objects, powder flasks.

In the autumn of 1648, the Cossack colonel Maxim Krivonos completely destroyed the castle after a six-week siege. Since then, the fortress has not been restored.

In 1793-1917, Kremenets was part of the Russian Empire. Since 1921, the city belonged to Poland, since 1939 - as part of the Ukrainian SSR.

The Jews of Kremenets are mentioned for the first time in the charter of the Grand Duke of Lithuania Svidrigailo dated 1438. They were forced to leave the city when the Jews were expelled from Lithuania in 1495, but returned a few years later, in 1503.

The Jewish population of Kremenets increased from 240 people (48 Jewish houses) in 1552 to 500 in 1578 and 854 (15% of the total population) in 1629. Among the property owned by Jews in 1563, a synagogue, a Jewish hospital and houses of shamash and rabbi are mentioned.

In the 16th and 17th centuries the Jewish community of Kremenets flourished. Prominent rabbis of the city during this period were Avraham Chazan, the author of Hibburei Leket (Selected Works), the prominent Halakhist Rabbi Mordechai Yaffe and Rabbi Shimshon ben Bezalel.

In 1569, according to the Union of Lublin, Kremenets passed to the Polish crown, and its community, as one of the main ones in the Volyn Voivodeship, became a member of the Vaad of Four Lands.

The death of many Jews of Kremenets in 1648-49 at the hands of the Cossacks B. Khmelnitsky led to the decline of the community. In 1650 she received a privilege from King Jan Casimir.

In 1765, 649 Jews lived in Kremenets; they were forbidden to rebuild houses destroyed by fire. During this period, a Hasidic community was formed in Kremenets, headed by rabbi Mordechai, the son of Yechiel Michael from Zlochev. Her main opponent was the local Maggid Yaakov Yisrael.

The Jewish population of Kremenets increased from 240 people (48 Jewish houses) in 1552 to 500 in 1578 and 854 (15% of the total population) in 1629. Among the property owned by Jews in 1563, a synagogue, a Jewish hospital and houses of shamash and rabbi are mentioned.

In the 16th and 17th centuries the Jewish community of Kremenets flourished. Prominent rabbis of the city during this period were Avraham Chazan, the author of Hibburei Leket (Selected Works), the prominent Halakhist Rabbi Mordechai Yaffe and Rabbi Shimshon ben Bezalel.

In 1569, according to the Union of Lublin, Kremenets passed to the Polish crown, and its community, as one of the main ones in the Volyn Voivodeship, became a member of the Vaad of Four Lands.

The death of many Jews of Kremenets in 1648-49 at the hands of the Cossacks B. Khmelnitsky led to the decline of the community. In 1650 she received a privilege from King Jan Casimir.

In 1765, 649 Jews lived in Kremenets; they were forbidden to rebuild houses destroyed by fire. During this period, a Hasidic community was formed in Kremenets, headed by rabbi Mordechai, the son of Yechiel Michael from Zlochev. Her main opponent was the local Maggid Yaakov Yisrael.

|

|

|

| Near the house. Photos of An-sky's expedition, 1912 | Jewish children in Kremenets. Photos of An-sky's expedition, 1912 | Synagogue Choir. Photo from the archive of the Sobol family |

The Jews of Kremenets suffered greatly from the civil strife of the Polish gentry, and by the time Kremenets was transferred to Russia in 1793, the Jewish community consisted of impoverished merchants and artisans. However, the discovery at the end of the 18th century Lyceum under the auspices of A. Czartoryski made Kremenets an attractive center of Polish culture, which gradually led to an improvement in the economic situation of the Jewish population.

The activities of I. B. Levinson turned the city into one of the centers of Haskala.

In 1897, the Jewish community of Kremenets numbered 6539 people (37% of the population).

Jews played an important role in the city's economy, in particular in the paper industry.

In 1910, there was a Talmud Torah in Kremenets, an elementary state Jewish men's school with a craft class, and a private women's school.

The activities of I. B. Levinson turned the city into one of the centers of Haskala.

In 1897, the Jewish community of Kremenets numbered 6539 people (37% of the population).

Jews played an important role in the city's economy, in particular in the paper industry.

In 1910, there was a Talmud Torah in Kremenets, an elementary state Jewish men's school with a craft class, and a private women's school.

In 1918–20 the population of Kremenets suffered from pogroms organized by gangs of Ukrainian nationalists, and from persecution by the Poles.

In 1933–39 published a weekly newspaper in Yiddish "Kremenitser Lebn".

In 1931, the Jewish population of Kremenets numbered 7256 people (36% of the total population).

In 1939, after the establishment of Soviet power in the city, Jewish cultural activities were banned.

By June 1941, the Jewish population of Kremenets increased by four thousand people due to refugees from German-occupied Poland.

In 1933–39 published a weekly newspaper in Yiddish "Kremenitser Lebn".

In 1931, the Jewish population of Kremenets numbered 7256 people (36% of the total population).

In 1939, after the establishment of Soviet power in the city, Jewish cultural activities were banned.

By June 1941, the Jewish population of Kremenets increased by four thousand people due to refugees from German-occupied Poland.

|

|

|

| Street in Kremenets, 1921. Photo by Alter Katsizne | Jewish inn in Kremenets | Trade Union House. Below you can see the inscription in Yiddish |

During the occupation of Kremenets by the Germans on July 22, 1941, hundreds of young Jews fled to the unoccupied regions of the Soviet Union. At the end of July 1941, about 800 Jews were killed by Ukrainian nationalists with the help of the Germans. The central synagogue was burned, and the Jews had to pay the Germans an indemnity in money and things. A Judenrat was created, whose chairman, Dr. Ben-Zion Katz, was executed by the Germans for refusing to provide lists of able-bodied Jews.

In 1942, a ghetto was organized in Kremenets.

Resistance groups were formed in the ghetto. On August 10, 1942, an uprising broke out in the ghetto, which was suppressed by the Germans on August 12.

On August 18–19, 1942, the inhabitants of the ghetto were shot near the railway station. During the deportation, many Jews chose to commit suicide by throwing themselves from balconies. Christian witnesses reported courageous behavior by Jews.

Shortly after the end of the war, Jews who returned from evacuation and demobilized from the Soviet army left for Poland, and from there to Israel and other countries of the world. In Israel, the USA and Argentina, there are communities of Jews from Kremenets.

According to the all-Ukrainian census of 2001, no Jews lived in Kremenets.

In 1942, a ghetto was organized in Kremenets.

Resistance groups were formed in the ghetto. On August 10, 1942, an uprising broke out in the ghetto, which was suppressed by the Germans on August 12.

On August 18–19, 1942, the inhabitants of the ghetto were shot near the railway station. During the deportation, many Jews chose to commit suicide by throwing themselves from balconies. Christian witnesses reported courageous behavior by Jews.

Shortly after the end of the war, Jews who returned from evacuation and demobilized from the Soviet army left for Poland, and from there to Israel and other countries of the world. In Israel, the USA and Argentina, there are communities of Jews from Kremenets.

According to the all-Ukrainian census of 2001, no Jews lived in Kremenets.

|

|

|

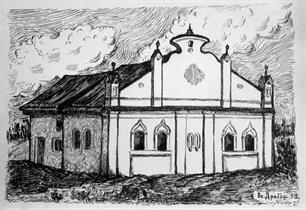

| Former Synagogue of the Dubno suburb, 2015 | Synagogue drawing in the Kremenets Museum, author Vsevolod Droban, 1959 |

One of the most beautiful buildings in the city, unfortunately, has not been preserved. On the facade you can see the advertisement of the photographer Peter Brodsky. Despite the non-Jewish name, the surname clearly talks about the origin of the photographer.

In addition to Brodsky, other Jewish photographers worked in Kremenets: Benzion Byk and Shmul Kirzhner.

In addition to Brodsky, other Jewish photographers worked in Kremenets: Benzion Byk and Shmul Kirzhner.

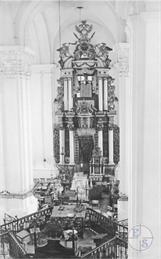

There were 18 synagogues and prayer houses in the city:

1) The synagogue in the Vishnevets suburb, in Fayvel Feldman's home.

2) Yisrael'ikl (Lerner)'s Synagogue in Moshe Kapuzer's home.

3) Mendil Rokhel's Synagogue on Slovatski Street.

4) The New Study Hall (Kazatske Study Hall) on Sheroka Street.

5) Yankele's Kloyz on Kladkova Street.

6) Bedrik's Kloyz on Kravatska Street.

7) The Tailors' Synagogue (Shnayder Shulkhel) on Kravatska Street.

8) The House of Prayer on Kladkova Street.

9) The Old Study Hall on Sheroka Street.

10) The Butchers' Synagogue (Katsavim Shtibel) on Butcher Shop Street.

11) The Synagogue of the Rozin Hasidim (Nishvitser Shulkhel) in Yitschak Bat's home.

12) The Hasidic Synagogue (Chasidish Shulkhel).

13) The Magid's Synagogue (Magid Shulkhel) in the courtyard of the Great Synagogue.

14) The Great Synagogue.

15) The Community Synagogue (Kahal Shulkhel) next to the Great Synagogue.

16) The Tailors' Synagogue (Shnayder Shulkhel) next to the Great Synagogue.

17) The Synagogue of the Dubno suburb.

18) Moshke'le's Synagogue.

There is only one of all building preserved in the town - former Synagogue of the Dubno suburb. This synagogue was rebuilt into a bus station.

1) The synagogue in the Vishnevets suburb, in Fayvel Feldman's home.

2) Yisrael'ikl (Lerner)'s Synagogue in Moshe Kapuzer's home.

3) Mendil Rokhel's Synagogue on Slovatski Street.

4) The New Study Hall (Kazatske Study Hall) on Sheroka Street.

5) Yankele's Kloyz on Kladkova Street.

6) Bedrik's Kloyz on Kravatska Street.

7) The Tailors' Synagogue (Shnayder Shulkhel) on Kravatska Street.

8) The House of Prayer on Kladkova Street.

9) The Old Study Hall on Sheroka Street.

10) The Butchers' Synagogue (Katsavim Shtibel) on Butcher Shop Street.

11) The Synagogue of the Rozin Hasidim (Nishvitser Shulkhel) in Yitschak Bat's home.

12) The Hasidic Synagogue (Chasidish Shulkhel).

13) The Magid's Synagogue (Magid Shulkhel) in the courtyard of the Great Synagogue.

14) The Great Synagogue.

15) The Community Synagogue (Kahal Shulkhel) next to the Great Synagogue.

16) The Tailors' Synagogue (Shnayder Shulkhel) next to the Great Synagogue.

17) The Synagogue of the Dubno suburb.

18) Moshke'le's Synagogue.

There is only one of all building preserved in the town - former Synagogue of the Dubno suburb. This synagogue was rebuilt into a bus station.

- Home

- Shtetls

- Vinnytsia region

- Volyn region

- Dnipro region

- Donetsk region

- Zhytomyr region

- Zakarpattia region

- Zaporizhzhia region

- Ivano-Frankivsk region

- Kyiv region

- Kropyvnytskyi region

- Luhansk region

- Lviv region

- Mykolayiv region

- Odessa region

- Poltava region

- Rivne region

- Sumy region

- Ternopil region

- Kharkiv region

- Kherson region

- Khmelnytskyi region

- Chernihiv region

- Chernivtsi region

- Cherkasy region

- Crimea

- Synagogues

- Cemeteries

- Objects & guides

- Gallery

- History

- Contact

Jewish towns of Ukraine

Jewish towns of Ukraine

My shtetl

My shtetl

Donate